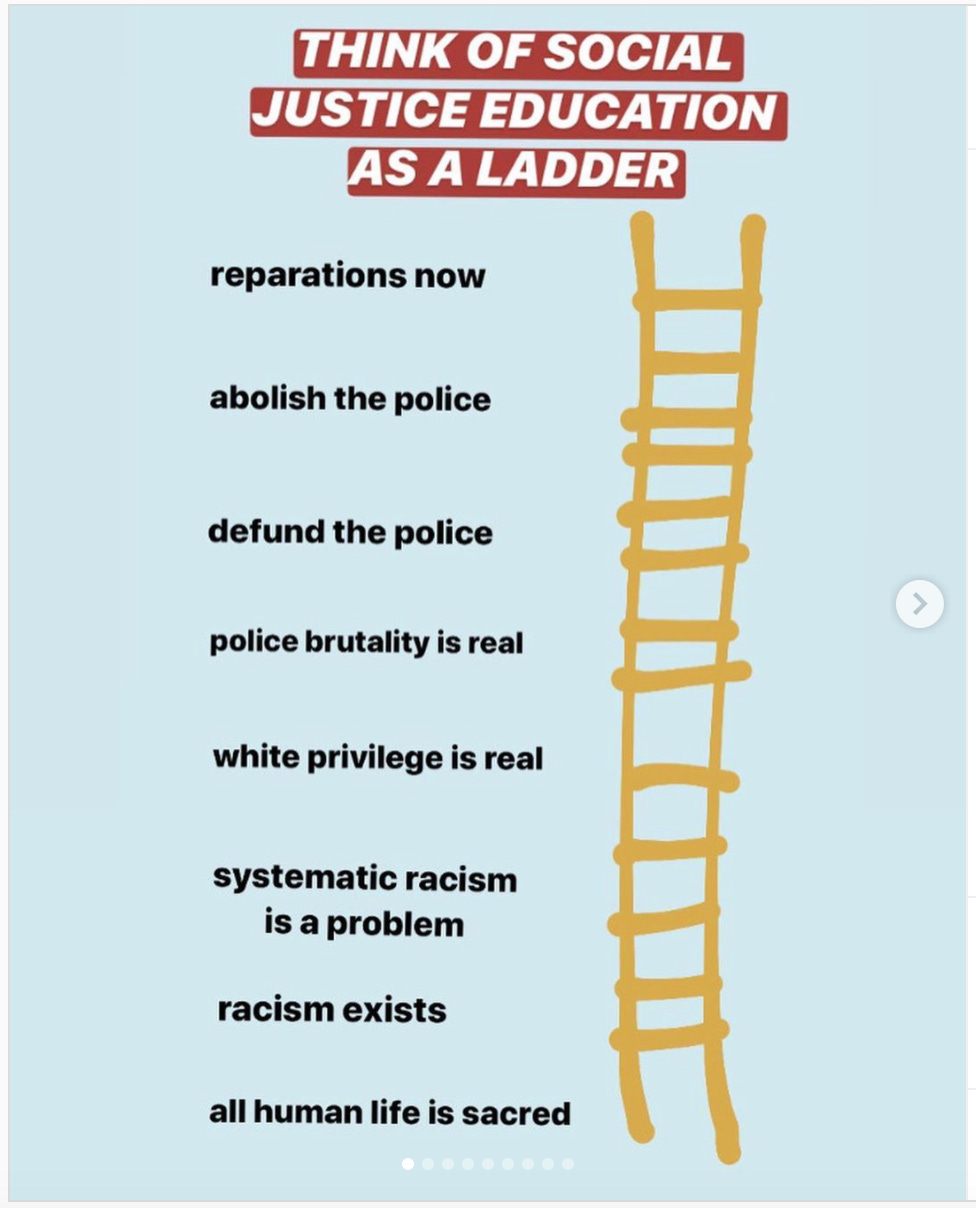

If calirock’s highway is a roadmap for social revolution, then _nanders’ ladder outlines the journey to personal (and maybe familial) revolution, or “enlightenment.”

_nanders’ zine (?) argues that social justice education, and corresponding jumps in thinking, works as a ladder. You move up from moderate to radical – “all human life is sacred” to “reparations now.” Like the highway, the ladder presents a linear journey but, unlike calirock’s highway, there is only one path; we’re all on this ladder, somewhere. Similarly, while there is no end to the highway, _nanders does reveal a “top” to the ladder: “enlightenment.”

But, she warns, jumping rungs on the ladder, from “systemic racism is a problem” to “abolish the police” for example, trips folks up, causing them to fall off. _nanders presents social justice, then, as a step-by-step process. The path to radicalism is slow-moving from accepted, universal truths (“all human life is sacred”) to more specific, radical understandings (“reparations now”). The ladder’s approach to education, and enlightenment, mirrors how we organize traditional schooling; a gradual series of classes which build on top of one other, increasing in intensity and depth each semester. Pre-Algebra, Algebra 1, Algebra 2, Pre-Calc, Calc AB, Calc BC.: “systemic racism is a problem,” “white privilege is real,” “police brutality is real,” “defund the police,” “abolish the police.” Up and up, rung by rung. This is a logical structure, if unintentional; we learn Algebra before Calculus and life science before biology and The Pearl before Beloved.

But I think, in my experience, _nanders’ ladder model falters in comparing social justice education to standard educational processes. For one, it’s dependent on us knowing where we are, or what grade we’re in, on the ladder. A “social justice education” doesn’t have classes or tests or certified teachers. There are no metrics tracking whether or not you’re a “good” ally. When thinking in terms of models like the ladder, it’s easy to start quantifying your allyship; if I read _______ books, I’ll be _______% less anti-racist. Our allyship slips; we prioritize personal “enlightenment” over collective liberation. Our allyship becomes centered on how we’re doing and ignores the material conditions and demands Black communities are fighting for. Even the concept of “enlightenment” is wrong-footed; there is no sudden epiphany out of race or racism and there is no test to pass or A to earn and there is no angel waiting to greet us at the gates of anti-racist heaven.

I can find it difficult not to quantify; it’s how most middle-class white kids have measured success and well-being our whole lives. Our wins have been evaluated in major milestones we could study and prepare for. We passed and moved up; SAT, AP tests, college apps, graduation, getting a job. We’ve been primed to think only in terms of our own personal success, or our family’s individual success, which capitalism and our preparation for a capitalist workplace have deemed quantifiable. But there is no “prize,” or metric to anchor ourselves here, nor should there be. We just need to keep doing the work and keep doing the work, actively. Erin Heaney, Director of SURJ, sums it up pretty well:

_nanders acknowledges the ladder’s limits – it occupies “a really tiny, meta corner of social justice to occupy, and is only the smallest sliver of the work that needs to be done.” I think she’s right; in an intro to ethnic studies course or in conversation with conservative relatives, the ladder approach seems to be the right mode to follow. My uncle in Idaho, for instance, might understand that “all human life is sacred,” and using this rung-like approach to talk more deeply about these issues with him, seems valuable.

But to apply traditional social justice education to a revolutionary moment seems impractical. We’re not in a traditional setting or a traditional time, and I don’t think we need our Republican uncle or ex-elementary school best friend to “wake up” before we defund the police and abolish the prison industrial complex and redirect those funds into other public services and communities. We can’t use the ladder as a model to procrastinate our direct involvement in collective activism. Movements (especially racial justice movements led by Black people) don’t have the leisure to wait in the wings until its allies are ready to activate. Even though pundits and moderate writers tip-toe around the word, we’re witnessing a revolution: a transfer of (social (and hopefully political and economic)) power from the ruling class to the masses or, as Trotsky defined, “the direct interference of the masses in historic events… the forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of rulership over their own destiny.” Revolutions have never been won because the bourgeoisie, or the CEOs or politicians or New York Times editors or police chiefs, one day “woke up” to injustice. (Even if they try to take credit for progressive action, after the fact.) Revolutions happen and are won because folks at the so-called “bottom,” or close to that “bottom,” develop consciousness of their own ability to collectivize and act. (Thanks, Shasun for reminding me of all of this!)

That’s what’s happening now. We’ve skipped rungs and rungs and rungs on the ladder in the past month, many of us jumping from “police brutality is real” to “reparations now” in days or even hours. White liberal consciousness, and petty-bourgeoisie consciousness (usually defined as the “lower middle-class”) more broadly, broke open overnight. A Civiqs poll shows that support for BLM moved up 11 points, to the majority of Americans, in a single month. Other surveys look the same. A Republican pollster exclaimed, “In my 35 years of polling, I’ve never seen opinion shift this fast or deeply. We are a different country today than just 30 days ago.”

This is what a revolution looks like. As Karl Marx argued, and generations of Black activists elaborated upon, revolution is the social leap. Paul D’Amato sums it up nicely: “Gradual accumulation of mass bitterness and anger of the exploited and oppressed bursts into a sudden mass movement to overturn existing social relations and replace them… A few days of revolution bring more change than decades of “normal” development.” History moves in a series of disruptions. The past is not a gradual process that evolves naturally: protests, strikes, and revolutions, all modes of disruption to the set social order, are what make history.

Yet it’s fool-hardy, and offensive to think that these movements are new, or Black lives are just mattering now because white folks are suddenly awake to it. Dialectics move in ebbs and flows: conflict builds for years (sometimes decades) before rupturing. As Dr. Angela Davis points out, in an interview with WBUR, “Black people have always been organized”; from Sunday school classes on slave plantations to the establishment of the Urban League and NAACP to BLM, “for hundreds of years, Black people have passed down this collective yearning for freedom from one generation to the next. We’re doing now what should’ve been done in the aftermath of slavery.”

For the past five years, (mostly local chapters of) Black Lives Matter have been organizing behind the scenes – building coalitions, strategizing, fundraising. Before them, this work was still being done by Black Americans, and before them, this work was still being done by Black Americans. Davis continues, “Many of us have been making the point for a very long time that activists who are truly committed to changing the world should recognize that the work we often do, that receives no public recognition, can eventually matter…The upsurge in activism that has happened as a result of the catalytic fact of the police murder of George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, and Tony McDade, and Rayshard Brooks, the response would not have been what it has become if people had not been doing on-the-ground work.”

Rebecca Solnit describes this type of explosive as “waterfalling”: rivers flow at a steady pace, but also swirl in rapids and shallows and can come “to the precipice and we’re all in the waterfall. Time accelerates, things change faster than anyone expected, water clear as glass becomes churning whitewater, what was thought to be impossible or the work of years is accomplished in a flash.” Solnit further specifies that our waterfall of activism, donations, support, etc. “followed Black Lives Matter; Black Lives Matter didn’t follow the support.”

Frederick Douglass also actively discussed, and analyzed, the “waterfalling” of social movements. Many of his speeches observe the rapid “rupturing” of white consciousness that occurred leading up to the Civil War, transforming some white northerners to abolitionists overnight. After the Dredd Scott vs. Sanford decision in 1857, which legally declared that Blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” and that slavery could expand anywhere in the nation, Douglass (correctly) argued in a rebuttal to the case that, with every pro-slavery court decision, the more anti-slavery (white) America became. He propped Dredd Scott up next to a series of other pro-slavery court decisions at the time (the Fugitive Slave Bill and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill primarily), which were becoming more frequent, and highlighted how with each consecutive decision, the white U.S. public reacted with increased agitation and abolition. Douglass argued that “the whole history of the anti-slavery movement is studded with proof that all measures devised and executed with a view to allay and diminish the anti-slavery agitation, have only served to increase, intensify, and embolden that agitation.” For Douglass, slavery, and the series of court decisions that legalized and attempted to hegemonize slavery, was so contradictory to the “natural essence of things,” or God’s will, and to the fabric of the “National Conscience,” that it tore a hole through America’s soul, blatantly revealing the country’s lies and falsehoods.

Whether or not we believe in a universal will of God or even a “National Conscience,” I think Douglass’ analysis still stands true. The tighter hegemony circles around folks, and contracts its tentacles, the more agitated the “double movement” (a term coined by economic historian Karl Polanyi) organizes in response.

In the first couple weeks of the BLM protests, police consistently escalated peaceful demonstrations with tear gas and rubber bullets and batons; in reaction, the double movement organized and strengthened. Hundreds of thousands of folks came out to the streets of LA and Boise and Houston and Tampa and Newark and hundreds of other big and small towns throughout the country (making it the largest protest in U.S. history). A lot of us marched for the first time, old and young, because justice seemed suddenly imperative; we couldn’t sit still. Never mind that race and racial injustice and police violence have been daily threats to Black people for the past 500 years.

Why did white people suddenly become aware of the violent institution they’ve been contributing to, and benefitting off of, for the history of the U.S.? Douglass believed that social movements and the individual people involved in these movements were inseparable; to rupture the mind of a man was to rupture the mind of a people. And only violence could rupture. Not violence against Black people (which led to a type of “gross sympathy”), but an internalized, violent war raged against white consciousness. White “awakening” needed to be violent — we needed to be shaken and prodded and thrown around the room. Douglass often discussed social and personal rupture in terms of natural disaster; volcanoes and hurricanes and earthquakes. These disasters are violent, but they’re also inevitable; they need to happen for the movement to move. We can’t just read Uncle Tom’s Cabin or White Fragility or Beloved or How to Be Antiracist — white people have to acknowledge their complicity in systems of racial violence head-on. Northerners felt far from slavery, we feel far from police violence, but these institutions only succeed because we agree with, and profit, however indirectly, from their infrastructure. We don’t need to learn about “social justice education” severed from the racial and economic conditions we live in and contribute to, Douglass argues, because we are very much in the muck of it. If we build the system, we need to break the system, and to break the system, we need to break us. And after we break, we need to actively move against it. This past month, a lot of us, for the first time, saw what the police really were: a useless organization of overpaid men with guns who protect property (mostly owned by white men), capital (mostly owned by white men), and the state (mostly governed by white men), while simultaneously gutting Black communities of any actual public safety, protection and economic wealth. The police have always been violent, have always incarcerated Black men, and have always protected property rights over human rights. None of this is new – except for us, now.

So what, now, “woke'“ us? I think it’s pretty simple: for the first time, we’re beginning to understand that our national identity is contradictory to historical truth. And by acknowledging this contradiction, we’re giving up any historical claim we can make on America and its wealth. Our history and identity, across every spectrum of whiteness, is, as Dr. Eddie S. Glaude, Jr writes in a New Yorker article detailing James Baldwin’s definition of “living history”, “bent in service of the lie.” “The lie” being that white Americans are exceptional and innately good, because America itself is innately exceptional and good. Baldwin saw this “lie,” as the corrupting force of the Nation: it had to be rooted out, internally and externally, for any real progress to be made. “All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history . . . which is not your past, but your present,” Baldwin said. “Your history has led you to this moment, and you can only begin to change yourself by looking at what you are doing in the name of your history.”

History for Baldwin, like history for Solnit and Marx and Davis and Douglass, is dialectical, rupturing, and external/internal: “History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read.” Baldwin wrote (and Glaude, Jr cites in his article). “And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us.” Of course we need to learn history in abstraction; of course we need to read historical accounts and analyses, learn the names and voices and ruptures, criticize what stories have survived. But that learning, to Baldwin, doesn’t undue racial capitalism or structural racism because we are still always producing and reproducing history (and thus racism) – now, sitting here, reading and writing this.

_nanders’ ladder tries to mitigate some of the uncomfortableness and jolting that Douglass and Baldwin see as necessary for social justice learning. Yet being jolted, often “violently,” is the learning. The ladder sees diluting Black Lives Matter’s message as a necessary evil to build a broader coalition of support.

This isn’t, historically, how most movements have been successful though. We know huge swaths of people change their minds overnight. We know broad public support for BLM followed “radical” calls to defund the police, refund communities, abolish the prison-industrial complex, etc. White people “awoke,” not to centrist calls for increased diversity or inclusion, but to a radical cry to re-structure how we protect, support, and invest in folks who have been disenfranchised for millennia.

This cry, importantly, was actionable and action-based. Marx believed that folks could only develop consciousness of their own power and potential collectively through the act of revolution itself. The struggle and its evolving form jolt us awake. “The alteration of men on a mass scale is necessary,” Marx and Engels wrote, “An alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary…because the class overthrowing [the ruling class] can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and became fitted to found society anew.” Only through struggle can we imagine and demand a better world. As we evolve and learn and grow, together, the horizons of what’s possible extend beyond our immediate conditions and limits.

Social justice learning, then, and “awakening” can’t start in individual vacuums of quantifiable syllabi – it can only happen through collective action. In “Emergent Strategy,” adrienne marie brown writes, “Emergence is beyond what the sum of its parts could even imagine.” Imagination is holistic — it’s togetherness. Moments of revolution allow for true seeing; they strip our vision, in a moment, of all the shit and barrenness and disinvestment and oppression we’ve come to understand as “normal” and allow us to see, and then imagine. Seeing is jolting, though, and does involve sacrifice, or the risk thereof. Baldwin wrote: "To act is to be committed and to be committed is to be in danger." White people need to be in danger. We need to be willing to give up material wealth and material power, or at least how we’ve come to understand material wealth and power. We need to imagine a culture that maybe doesn’t include my job as an investment banker or my eight-bedroom house with a pool or my three Teslas. It’s terrifying to think of ourselves outside of our rotting system because all we know is our rotting system. But abandoning power revives — we’re alive! The radical becomes possible and the possible becomes tangible. We’re close.

this really helped me understand why the movement seems to be changing peoples' minds this time around. it still scares me that people will do anything to protect white, colonialist mindsets at the cost of anything. as always, your closing statements are so beautiful, nils.