Ally Math

This graphic is dumb. Or maybe it’s a poem. If so – dumb poem!

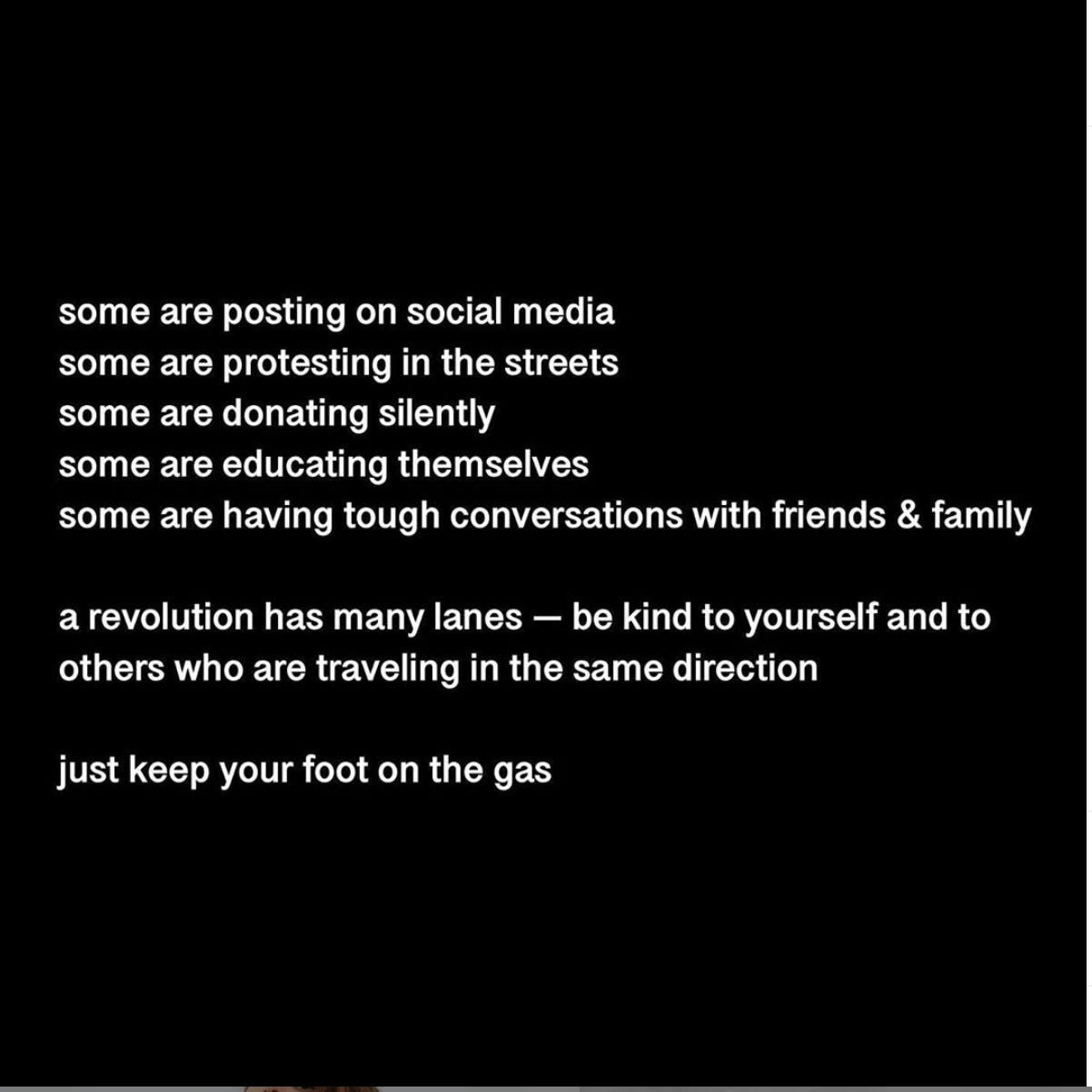

By repeating “some,” and interchanging the following predicate with a drop-down list of actions, Instagram user calirock levels each "action equally. The subject–the pronoun “some”-stays static while the predicate–the action–changes. Anyone could be “some” and, calirock argues, any revolutionary is a part of some “some.” And each “some,” seemingly, sums up to a whole; some + some + some + some + some = revolution. You don’t have to be the revolution, just “some” of the revolution.

But through the repetition of “some,” calirock assumes, literally, that each “some” is equivalent to another “some”; they’re the same word. “Some are posting on social media,” “some are protesting in the streets”; to-mato, to-motto. Her equation shifts: some = some = some = some = some = revolution. Each line’s parallel structure repeats this equality: subject and predicate, subject and predicate. Without hierarchy, the proposed actions, “posting” or “protesting” or “donating” or “educating” or “having,” carry the same syntactical weight. Instead of addition, calirock advocates equality.

But we know that “posting” does not equal “protesting” does not equal “donating” does not equal “educating” does not equal “having.” By equating these “actions” to one another, calirock warps their scale of effort and impact. Someone is doing all these things, they are actions. But the extent to which one is doing that thing, and what doing that thing costs, differ. Protesting requires significantly more doing than re-posting an Instagram zine and donating requires direct doing now while educating involves external or internal doing, often indirectly, over a series of years or even decades. “Having tough conversations” is direct doing but with, immediately or long-term, a familial impact. Some of these actions are direct, some just hang out. Some require you to put your body and voice on the line in for others, even sacrifice relationships, some don’t require you to get out of bed. “A revolution has many lanes,” but the impact, and effort, behind each in unequal.

What do these lanes look like and how does this road move? It’s one-way, but the “posting” lane is thinner than the “donating” lane. The “educating” and “having” lanes are pretty big. The “protesting” lane holds the most cars — buses fit too. The traffic regularly over-congests in “posting,”, forcing drivers into “donating” or even “educating”, and maybe all the way over to “protesting.” But “protesting” is carpool; the more people you fit, the better. Sometimes the road narrows, consolidating, and sometimes it expands, painting new lines to make new lanes to fit new cars; lanes for mutual aid, art displays, voting, etc.

There’s a lot of swerving. And here’s where calirock’s metaphor falls apart. The traffic lane metaphor succeeds only so far as the lanes are clearly marked and divided. If we swerve back and forth, we crash. We instead stay in one lane, slowly sliding our blinker on before we go-between.

This is also why “some” is such a weak pronoun – it advocates for a type of fragmented collectivism, divided by “lanes.” “We” or “us” or even “they” points toward one group or movement, united even in its subtasks, while “some” isolates. “Some” is vague in its accountability. “We” or “us” include the speaker in the action whereas “some” distances the speaker, high atop Pride Rock gazing down at those “posting” and those “educating,” etc., viewing but not participating.

So, what happens to the road if we’re “posting” + “protesting” + “donating” + “educating” + “having?” Does the car zig and zag or transform into a 25-foot-wide limo, taking over the whole highway? Are we now in a train? What’s the speed limit? Are there fast lanes and slow lanes? There must be; “educating” supposedly moves slow and meticulously, “having” is bumpy, “donating” stops and starts, “protesting” zooms messily, and “posting” only allows electric vehicles. Where’s our destination? Or is the highway in an eternal loop, Rainbow Road-ing around the globe? Are there traffic signs, announcing how close you are to, well, something? Enlightenment?

No, I don’t think so – crashes are inevitable. The idea that you have your lane to do your due diligence feels wrong-headed and alleviating. We should be “posting” and “protesting” and “donating” and “educating” and “having,” and we should be aware of what the impact, and effort, of each action, is. Take “posting.” “Posting” has made organizing easier; the dissemination of concepts like prison abolition and antiracism, not by the bourgeoisie, but by everyday folks, is way more accessible now than when my parents were kids. Instagram is tumbling with advocacy toolkits, elected officials’ phone numbers, protest information and details, lists on lists of black-owned businesses. But “posting” is not a political good in itself. It doesn’t help anyone unless it’s acted upon in the public realm. We hope our followers will act or donate or support but how do we trace impact? Views might equal reach, but they don’t equate to outcome. Our posts loiter, waiting for something to do.

To do what calirock does and equalize “posting” with “protesting” or even “donating” or “educating” or “having” misconstrues the effort and outcome of each. This mode of thought allows (usually white) allies to retweet a meme and call it a day because we’ve designated “posting” as our lane, while expecting other folks to put their bodies in front of police SUVs or rubber bullets or COVID-19, because we assume that “protesting” is their designated lane. This is dangerous because the communities fighting on the front lines are usually the folks whose lives and livelihood are most at stake. They’re fighting for their lives and we’re asking them to take on the burden of risk while we “post” or “educate” or “have.” Any support is essential, but these different types of support (“protesting,” “posting,” “donating,” etc.), or “action,” are unequally distributed. In a way, we’re reproducing the same unequal systems of power, in our allyship, we’re supposedly fighting against. We support, but we displace the burden of work, struggle, and violence onto the same communities of color we claim to be standing up for.

You might call this “support” “optical allyship” but that seems too easy of a term to use here because these “posts” and “donations” and reading lists aren’t empty or self-serving; they’re good-natured and informative. We want to learn, and we want to help each other learn. I love the cute zines detailing what a world without police might look like. But sharing these posts and educating ourselves and talking to our family doesn’t replace direct action and mutual aid. It’s a yes, and! Yes, I will post and hand out waters at that Grand Park rally. Yes, I’ll read The New Jim Crow and I will donate to Black Trans Femmes in the Arts Collective and email Nury Martinez and join a multi-racial coalition. In other words, we need to have a car driving in each lane.

calirock hypothesizes that this “doing everything” mentality will result in exhaustion. At the end of her post, she argues that her “highway” metaphor serves as an alternative to burnout. “Be kind to yourself,” she pleads; choose a lane because, either way, you’re still doing the work.

But being kind to yourself isn’t mutually exclusive to burnout. White people might be exhausted because de-centering ourselves from narratives and social action involves work most of us are unaccustomed to. But fuck – it’s been a month! Burnout, and keep going. Your gas may run out, your foot might cramp, you might crash. But crash, pick yourself up out of the rubble and get up and walk. By siloing “revolution” into lanes, calirock reinforces the structures of individual success that have undermined collective action and liberation for decades. Do it all and keep doing it. Revolutions are work, and they’re often violent, but they are also love. They rejuvenate. Movements are reparative and regenerative; self-love isn’t an alternative or “break” from revolution, it is revolution.